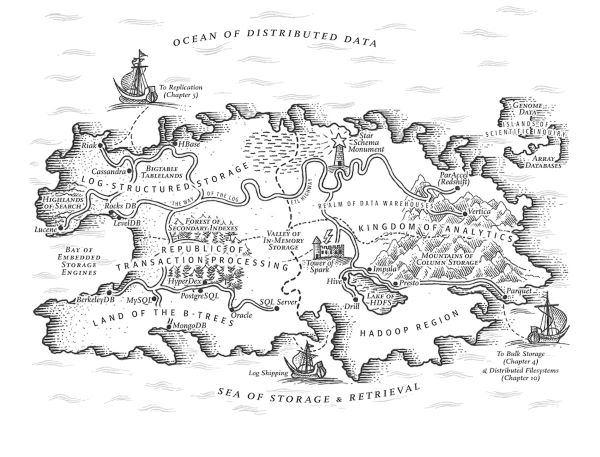

Designing Data-Intensive Applications by Martin Kleppmann was not a quick-read. Let me be clear, it is not such a long book (the paper version is 400 pages), but it is so dense of information that takes some time to go through. The book covers indeed a broad spectrum of data technologies and is dense of details in each paragraph. So, be ready before starting the journey.

What did I learn from the book? I'll take few quotes from my notes.

An architecture that is appropriate for one level of load is unlikely to cope with 10 times that load. If you are working on a fast-growing service, it is therefore likely that you will need to rethink your architecture on every order of magnitude load increase — or perhaps even more often than that.

We need to be able to test, develop, and change quickly our architecture. The book covers the main data solution designs, but you need a team and an organizaiton that is able to adapt and improve the architecture constantly. And more importantly, avoid premature optimization as much as possible. Prefer simplicity over complexity.

If the same query can be written in 4 lines in one query language but requires 29 lines in another, that just shows that different data models are designed to satisfy different use cases. It’s important to pick a data model that is suitable for your application.

Don't focus on data processing performance only, data models and query languages do matter. The overall simplicity and readability of the solution design should be taken into account when choosing the data model.

On the surface, a data warehouse and a relational OLTP database look similar, because they both have a SQL query interface. However, the internals of the systems can look quite different, because they are optimized for very different query patterns. Many database vendors now focus on supporting either transaction processing or analytics workloads, but not both.

We experienced this difference in my team. We started by building a data warehouse on top of SQL, but we run into performance issues quite soon. The statement by Kleppmann may seem obvious, but there are plenty of organization building data warehouses on SQL for a variety of reasons.

... we will explore some of the most common ways how data flows between processes: via databases, via service calls (eg REST and RPC), and via asynchronous message passing (eg MQTT, AMQP).

I find this an amazing summary. In the end, any data flow architecture falls in one these 3 categories, isn't it true?

When you deploy a new version of your application (of a server-side application, at least), you may entirely replace the old version with the new version within a few minutes. The same is not true of database contents: the five-year-old data will still be there, in the original encoding, unless you have explicitly rewritten it since then. This observation is sometimes summed up as data outlives code.

Migrating data is harder than updating an application (and there are richer tools available for deploying an application than migrating a database).

May your application’s evolution be rapid and your deployments be frequent.

I love this wish 😊

All of the difficulty in replication lies in handling changes to replicated data, and that’s what this chapter is about. We will discuss three popular algorithms for replicating changes between nodes: single-leader, multi-leader, and leaderless replication. Almost all distributed databases use one of these three approaches.

I found this quote in the introduction to the Replication chapter of the book. I heard often mentioning these replication mechanism, but for the first time I did a deep dive in the topic (that is not as easy as I would have expected). Kleppmann throughout the book makes you clear one thing: there are many things that can go wrong around data (timestamp alignment, networking, nodes down, etc), and they will go wrong at some point.

Because of this risk of skew and hot spots, many distributed datastores use a hash function to determine the partition for a given key. A good hash function takes skewed data and makes it uniformly distributed.

And fortunately this hashing is often managed under the hood by datastores themselvs, eg Azure Cosmos.

Atomicity, isolation, and durability are properties of the database, whereas consistency (in the ACID sense) is a property of the application. The application may rely on the database’s atomicity and isolation properties in order to achieve consistency, but it’s not up to the database alone. Thus, the letter C doesn’t really belong in ACID.

Interesting to read that the C in such a popular acronym is there just to make the acronym work.

Errors will inevitably happen, but many software developers prefer to think only about the happy path rather than the intricacies of error handling.

True story, but experience helps thinking a bit more to the sad path.

Simply dumping data in its raw form allows for several such transformations. This approach has been dubbed the sushi principle: "raw data is better"

I have been following the sushi principle in the last year without being aware of this definition. Nice name!

Database triggers can be used to implement change data capture by registering triggers that observe all changes to data tables and add corresponding entries to a changelog table. However, they tend to be fragile and have significant performance overheads. Parsing the replication log can be a more robust approach, although it also comes with challenges, such as handling schema changes.

I see replication log parsing as a growing trend. It enables the method "take data to datalake and then we'll see what to do". Furthermore, it fits for steaming data applications too. Today, not all vendors support the publication of such change logs natively (eg I didn't find a simple solution for SQL Server).

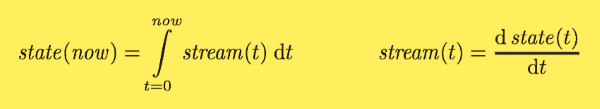

If you are mathematically inclined, you might say that the application state is what you get when you integrate an event stream over time, and a change stream is what you get when you differentiate the state by time, as shown in figure. The analogy has limitations (for example, the second derivative of state does not seem to be meaningful), but it’s a useful starting point for thinking about data.

This brilliant analogy is the intro of the chapter I enjoyed the most within the entire book, ie the Stream Processing chapter. It represents a database as the latest cache representing the replication logs (the opposite point of view we normally have).

In the absence of widespread support for a good distributed transaction protocol, I believe that log-based derived data is the most promising approach for integrating different data systems.

I have seen Kafka as a tool for stream processing so far. I was not thinking of it as a tool for integrating data systems. The last chapter of the book gives a hint on how log-based derived data may become a popular pattern soon.

The trend has been to keep stateless application logic separate from state management (databases): not putting application logic in the database and not putting persistent state in the application. As people in the functional programming community like to joke, "We believe in the separation of Church and state"

Good one.